The AA battery—also called a double A or Mignon (French for 'dainty') battery—is a. Face cards or court cards – jacks, queens and kings. Honour cards - aces and the face cards. Wild cards – When deciding which cards are to be made wild in some games, the phrase 'acey, deucey or one-eyed jack ' (or 'deuces, aces, one-eyed. Numerals or pip cards are the cards numbered.

Playing cards are known and used the world over—and almost every corner of the globe has laid claim to their invention. The Chinese assert the longest pedigree for card playing (the 'game of leaves' was played as early as the 9th century). The French avow their standardization of the carte à jouer and its ancestor, the tarot. And the British allege the earliest mention of a card game in any authenticated register.

Today, the public might know how to play blackjack or bridge, but few stop to consider that a deck of cards is a marvel of engineering, design, and history. Cards have served as amusing pastimes, high-stakes gambles, tools of occult practice, magic tricks, and mathematical probability models—even, at times, as currency and as a medium for secret messages.

In the process, decks of cards reveal peculiarities of their origins. Card names, colors, emblems, and designs change according to their provenance and the whims of card players themselves. These graphic tablets aren't just toys, or tools. They are cultural imprints that reveal popular custom.

* * *

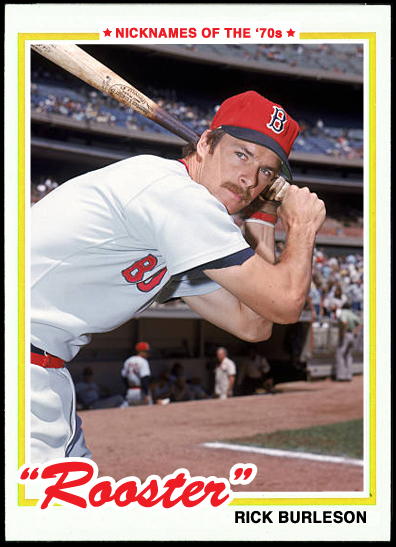

List Of Playing Card Nicknames

The birthplace of ordinary playing cards is shrouded in obscurity and conjecture, but—like gunpowder or tea or porcelain—they almost certainly have Eastern origins. 'Scholars and historians are divided on the exact origins of playing cards,' explains Gejus Van Diggele, the chairman of the International Playing-Card Society, or IPCS, in London. 'But they generally agree that cards spread from East to West.'

More in this series

Candy Land Was Invented for Polio Wards

Alexander B. Joy

Scrolls from China's Tang Dynasty mention a game of paper tiles (though these more closely resembled modern dominoes than cards), and experts consider this the first written documentation of card playing. A handful of European literary references in the late 14th century point to the sudden arrival of a 'Saracen's game,' suggesting that cards came not from China but from Arabia. Yet another hypothesis argues that nomads brought fortune-telling cards with them from India, assigning an even longer antiquity to card playing. Either way, commercial opportunities likely enabled card playing's transmission between the Far East and Europe, as printing technology sped their production across borders.

In medieval Europe, card games occasioned drinking, gambling, and a host of other vices that drew cheats and charlatans to the table. Card playing became so widespread and disruptive that authorities banned it. In his book The Game of Tarot, the historian Michael Dummett explains that a 1377 ordinance forbade card games on workdays in Paris. Similar bans were enacted throughout Europe as preachers sought to regulate card playing, convinced that 'the Devil's picture book' led only to a life of depravity.

Everybody played cards: kings and dukes, clerics, friars and noblewomen, prostitutes, sailors, prisoners. But the gamblers were responsible for some of the most notable features of modern decks.

Today's 52-card deck preserves the four original French suits of centuries ago: clubs (♣), diamonds (♦), hearts (♥), and spades (♠). These graphic symbols, or 'pips,' bear little resemblance to the items they represent, but they were much easier to copy than more lavish motifs. Historically, pips were highly variable, giving way to different sets of symbols rooted in geography and culture. From stars and birds to goblets and sorcerers, pips bore symbolic meaning, much like the trump cards of older tarot decks. Unlike tarot, however, pips were surely meant as diversion instead of divination. Even so, these cards preserved much of the iconography that had fascinated 16th-century Europe: astronomy, alchemy, mysticism, and history.

Poker Card Nicknames

Some historians have suggested that suits in a deck were meant to represent the four classes of Medieval society. Cups and chalices (modern hearts) might have stood for the clergy; swords (spades) for the nobility or the military; coins (diamonds) for the merchants; and batons (clubs) for peasants. But the disparity in pips from one deck to the next resists such pat categorization. Bells, for example, were found in early German 'hunting cards.' These pips would have been a more fitting symbol of German nobility than spades, because bells were often attached to the jesses of a hawk in falconry, a sport reserved for the Rhineland's wealthiest. Diamonds, by contrast, could have represented the upper class in French decks, as paving stones used in the chancels of churches were diamond shaped, and such stones marked the graves of the aristocratic dead.

The AA battery—also called a double A or Mignon (French for 'dainty') battery—is a. Face cards or court cards – jacks, queens and kings. Honour cards - aces and the face cards. Wild cards – When deciding which cards are to be made wild in some games, the phrase 'acey, deucey or one-eyed jack ' (or 'deuces, aces, one-eyed. Numerals or pip cards are the cards numbered.

Playing cards are known and used the world over—and almost every corner of the globe has laid claim to their invention. The Chinese assert the longest pedigree for card playing (the 'game of leaves' was played as early as the 9th century). The French avow their standardization of the carte à jouer and its ancestor, the tarot. And the British allege the earliest mention of a card game in any authenticated register.

Today, the public might know how to play blackjack or bridge, but few stop to consider that a deck of cards is a marvel of engineering, design, and history. Cards have served as amusing pastimes, high-stakes gambles, tools of occult practice, magic tricks, and mathematical probability models—even, at times, as currency and as a medium for secret messages.

In the process, decks of cards reveal peculiarities of their origins. Card names, colors, emblems, and designs change according to their provenance and the whims of card players themselves. These graphic tablets aren't just toys, or tools. They are cultural imprints that reveal popular custom.

* * *

List Of Playing Card Nicknames

The birthplace of ordinary playing cards is shrouded in obscurity and conjecture, but—like gunpowder or tea or porcelain—they almost certainly have Eastern origins. 'Scholars and historians are divided on the exact origins of playing cards,' explains Gejus Van Diggele, the chairman of the International Playing-Card Society, or IPCS, in London. 'But they generally agree that cards spread from East to West.'

More in this series

Candy Land Was Invented for Polio Wards

Alexander B. Joy

Scrolls from China's Tang Dynasty mention a game of paper tiles (though these more closely resembled modern dominoes than cards), and experts consider this the first written documentation of card playing. A handful of European literary references in the late 14th century point to the sudden arrival of a 'Saracen's game,' suggesting that cards came not from China but from Arabia. Yet another hypothesis argues that nomads brought fortune-telling cards with them from India, assigning an even longer antiquity to card playing. Either way, commercial opportunities likely enabled card playing's transmission between the Far East and Europe, as printing technology sped their production across borders.

In medieval Europe, card games occasioned drinking, gambling, and a host of other vices that drew cheats and charlatans to the table. Card playing became so widespread and disruptive that authorities banned it. In his book The Game of Tarot, the historian Michael Dummett explains that a 1377 ordinance forbade card games on workdays in Paris. Similar bans were enacted throughout Europe as preachers sought to regulate card playing, convinced that 'the Devil's picture book' led only to a life of depravity.

Everybody played cards: kings and dukes, clerics, friars and noblewomen, prostitutes, sailors, prisoners. But the gamblers were responsible for some of the most notable features of modern decks.

Today's 52-card deck preserves the four original French suits of centuries ago: clubs (♣), diamonds (♦), hearts (♥), and spades (♠). These graphic symbols, or 'pips,' bear little resemblance to the items they represent, but they were much easier to copy than more lavish motifs. Historically, pips were highly variable, giving way to different sets of symbols rooted in geography and culture. From stars and birds to goblets and sorcerers, pips bore symbolic meaning, much like the trump cards of older tarot decks. Unlike tarot, however, pips were surely meant as diversion instead of divination. Even so, these cards preserved much of the iconography that had fascinated 16th-century Europe: astronomy, alchemy, mysticism, and history.

Poker Card Nicknames

Some historians have suggested that suits in a deck were meant to represent the four classes of Medieval society. Cups and chalices (modern hearts) might have stood for the clergy; swords (spades) for the nobility or the military; coins (diamonds) for the merchants; and batons (clubs) for peasants. But the disparity in pips from one deck to the next resists such pat categorization. Bells, for example, were found in early German 'hunting cards.' These pips would have been a more fitting symbol of German nobility than spades, because bells were often attached to the jesses of a hawk in falconry, a sport reserved for the Rhineland's wealthiest. Diamonds, by contrast, could have represented the upper class in French decks, as paving stones used in the chancels of churches were diamond shaped, and such stones marked the graves of the aristocratic dead.

Nicknames For Cards

But how to account for the use of clover, acorns, leaves, pikes, shields, coins, roses, and countless other imagery? 'This is part of the folklore of the subject,' Paul Bostock, an IPCS council member, tells me. 'I don't believe the early cards were so logically planned.' A more likely explanation for suit marks, he says, is that they were commissioned by wealthy families. The choice of pips is thus partly a reflection of noblemen's tastes and interests.

* * *

While pips were highly variable, courtesan cards—called 'face cards' today—have remained largely unchanged for centuries. British and French decks, for example, always feature the same four legendary kings: Charles, David, Caesar, and Alexander the Great. Bostock notes that queens have not enjoyed similar reverence. Pallas, Judith, Rachel, and Argine variously ruled each of the four suits, with frequent interruption. As the Spanish adopted playing cards, they replaced queens with mounted knights or caballeros. And the Germans excluded queens entirely from their decks, dividing face cards into könig (king), obermann (upper man), and untermann (lower man)—today's Jacks. The French reintroduced the queen, while the British were so fond of theirs they instituted the 'British Rule,' a variation that swaps the values of the king and queen cards if the reigning monarch of England is a woman.

The ace rose to prominence in 1765, according to the IPCS. That was the year England began to tax sales of playing cards. The ace was stamped to indicate that the tax had been paid, and forging an ace was a crime punishable by death. To this day, the ace is boldly designed to stand out.

The king of hearts offers another curiosity: The only king without a mustache, he appears to be killing himself by means of a sword to the head. The explanation for the 'suicide-king' is less dramatic. As printing spurred rapid reproduction of decks, the integrity of the original artwork declined. When printing blocks wore out, Paul Bostock explains, card makers would create new sets by copying either the blocks or the cards. This process amplified previous errors. Eventually, the far edge of our poor king's sword disappeared.

Hand craftsmanship and high taxation made each deck of playing cards an investment. As such, cards became a feast for the eye. Fanciful, highly specialized decks offered artists a chance to design a kind of collectible, visual essay. Playing-card manufacturers produced decks meant for other uses beyond simple card playing, including instruction, propaganda, and advertising. Perhaps because they were so prized, cards were often repurposed: as invitations, entrance tickets, obituary notes, wedding announcements, music scores, invoices—even as notes between lovers or from mothers who had abandoned their babies. In this way, the humble playing card sometimes becomes an important historical document, one that offers both scholars and amateur collectors a window into the past.

While collectors favored ornate designs, gamblers insisted on standard, symmetrical cards, because any variety or gimmickry served to distract from the game. For nearly 500 years, the backs of cards were plain. But in the early 19th century, Thomas De La Rue & Company, a British stationer and printer, introduced lithographic designs such as dots, stars, and other simple prints to the backs of playing cards. The innovation offered advantages. Plain backs easily pick up smudges, which 'mark' the cards and make them useless to gamblers. By contrast, pattern-backed cards can withstand wear and tear without betraying a cardholder's secrets.

Years later, Bostock tells me, card makers added corner indices (numbers and letters), which told the cardholder the numerical value of any card and its suit. This simple innovation, patented during the Civil War, was revolutionary: Indices allowed players to hold their cards in one hand, tightly fanned. A furtive glance offered the skilled gambler a quick tally of his holdings, that he might bid or fold or raise the ante, all the while broadcasting the most resolute of poker faces.

Standard decks normally contain two extra 'wild' cards, each depicting a traditional court jester that can be used to trump any natural card. Jokers first appeared in printed American decks in 1867, and by 1880, British card makers had followed suit, as it were. Curiously, few games employ them. For this reason, perhaps, the Joker is the only card that lacks a standard, industry-wide design. He appears by turns the wily trickster, the seducer, the wicked imp—a true calling card for the debauchery and pleasure that is card playing's promise.

Suicide King

The King of Hearts is usually depicted with a sword, although earlier decks often featured him with a battle axe. He is typically referred to as the 'suicide king' because on a traditional deck he is pictured as stabbing himself with a sword, or at least holding a sword behind his head. Even many custom decks will adopt this idea, with variations according to the theme of the deck. The King of Hearts is the only king without a moustache, but unfortunately we simply don't know for sure how that difference originated.

Man With the Axe

This designation for the King of Diamonds reflects the fact that this is the only king not carrying a sword. Kings are sometimes also referred to generally as 'cowboys'.

Black Lady

The nickname 'Black Lady' for the Queen of Spades is closely connected with the game of Hearts, which is often referred to with alternative names like Black Lady, Black Maria, and Black Widow. In this trick-taking game, the idea is to avoid collecting points, with Hearts cards all worth one point each, while the Queen of Spades (sometimes dubbed 'Calamity Jane' in this context) costs a massive 13 penalty points. Other names for this card include Bedpost Queen, Dirty Gertie, and Molly Hogan. She usually is pictured holding a sceptre.

Flower Queen

The Queen of Clubs is known as the 'flower queen' for an obvious reason - she is usually depicted holding a flower. Some decks picture all the Queens with flowers, with the style adjusted according to their suit.

Laughing Boy

Jacks are also called Knaves, and are inferior to the more regal Kings and Queens, making them more playful. The Jack of Diamonds is known as the Laughing Boy, and in some variations of Poker and Black Jack, players are expected to chuckle every time this card is played or drawn.

Curse of Scotland

The Scots consider the Nine of Diamonds to be an unlucky card, and its nickname goes back to the 18th century. Why? We can't be entirely sure, and several different ideas have been suggested. One possibility speculates that the orders for the Glencoe Massacre of 1692 ('Kill them all', which resulted in the slaying of 38 Highlanders), were written on a Nine of Diamonds card. It's also been noted that Secretary of State Sir John Dalrymple, who contributed to this massacre, had a coat of arms with nine diamond-like shapes.

Beer Card

This designation for the Seven of Diamonds appears to have originated in the mid-1900s in Denmark, and is used in trick-taking games like Bridge. As an unofficial and optional side-bet, the partner of a player who wins the last trick of a hand with a Seven of Diamonds must buy him a beer.

The Devil's Bedpost

Also called the Devil's Four-Poster Bed, this name for the Four of Clubs is derived from the design of the pips on the card, which can be imagined to be the four posts of a bed. This card is considered by some superstitious folk to be a curse, apparently ruining any hand that includes it.

Death Card

Traditionally the Ace is the highest ranking card, but this card's actual value can vary on the game played. The Ace of Spades is commonly referred to as the Death Card, although the exact origin of this name can't be identified with complete certainty. Is there a connection with the fact that this was the card designated to be marked with a tax stamp in England in the 1800s? During this time, forgery of an Ace of Spades was considered a capital crime punishable by death. Or is there truth to the legend popularized in many films about the Vietnam War? It has been suggested that the Viet Cong was so terrified by the Ace of Spades, that American soldiers used it to frighten their enemy by wearing it on their helmets and by leaving it on dead bodies. Perhaps the origin of the term is much simpler: a spade is also a shovel, an instrument commonly associated with digging graves.

One-Eyed Jacks

Unlike most of the other court cards, the Jack of Spades and the Jack of Hearts both have a side profile, hence their designation as 'one-eyed Jacks'. The only King facing sideways is the King of Diamonds, and together with the Jack of Spades and the Jack of Hearts, these three cards are sometimes referred to as the one-eyed royals.

More Name-calling

Court cards: There was a trend during the 15th century for French card manufacturers to designate the court cards as literary and historical figures. There was never an adopted standard, but certain personages were commonly used in this time. As a result, the Kings are also sometimes called David (Spades), Charlemagne or Charles (Hearts), Julius Caesar (Diamonds), and Alexander (Clubs); the Queens are sometimes called Athena (Spades), Judith (Hearts), Rachel (Diamonds), and Argine (Clubs); while the Jacks are sometimes called Ogier or Eunuch (Spades), La Hire (Hearts), Hector (Diamonds), and Lancelot (Clubs).

Card combinations: There are also many common terms for particular card combinations, many of which originate with Poker. For example the 'Dead Man's Hand' is said to be the hand held by gunfighter 'Wild Bill' Hickok when he was murdered, and contained two black Aces and two black Eights. A pair of Aces can be dubbed as 'Pocket Rockets' or 'Snake Eyes', while the King-Ace combination is frequently known as 'Big Slick'. Countless others nicknames for specific card combinations exist.

Watch your language! Many terms from the world of playing cards have also entered the English language. For a long list, see this previously published article: The Impact of Playing Cards on the English language. Many of these terms originate from trick taking games or poker. The fact that expressions like 'follow suit', 'have a card up your sleeve', and 'come up trumps' are commonly used and understood by almost everyone, says a lot about the popularity of playing cards, and their impact on culture generally.

Other nicknames: The above list is by no means complete. There are many localized nicknames, and virtually every playing card has acquired a nickname or even multiple names at some point in history. For example, the Joker is also called by names like Wildcard, Trump Card, Best Bower, The Fool, and The Bird. You'll find an exhaustive list of playing card nicknames over on Wikipedia (link).

Giving playing cards names shows that they are a big part of our life. When we think about a deck of cards, we aren't just thinking about 52 pieces of cardboard, but our friends at the card table or our accomplices in a magic trick. The good news is that this means that when you add a new deck to your collection, it's not really a matter of wasteful spending, but an exercise in getting 52 new friends!

Author's note: I first published this article at PlayingCardDecks.com here.